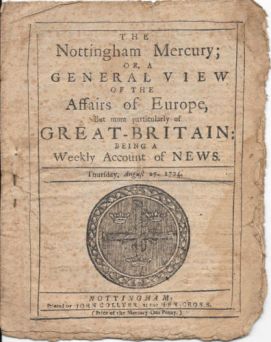

Eighteenth-century news sources are most readily accessible through large digital databases such as the Burney collection and the British Newspaper Archive, which require institutional or personal subscription to access. There is, however, a small collection of newspaper issues for the late 1730s freely available through Google Books, although it is not identified as such. This anomaly has occurred due to digital indexing practices and the unusual and ephemeral nature of the original source material.

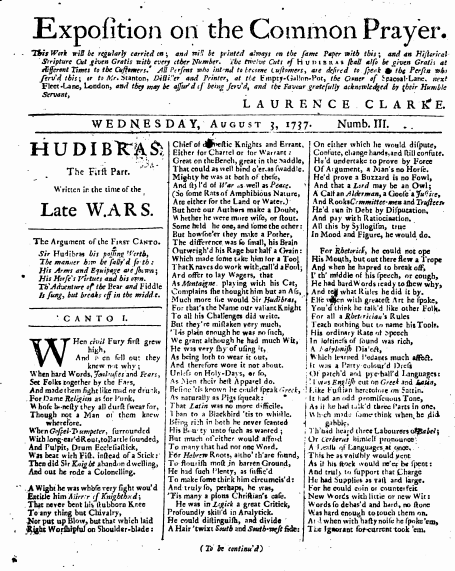

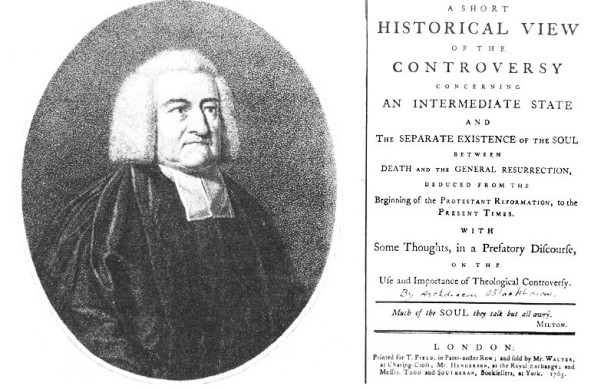

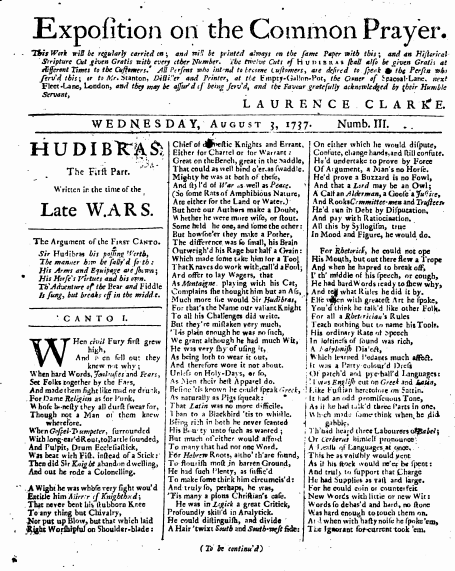

Google Books identifies the ‘book’ in question as an obscure theological work, ‘Exposition on the Common prayer’ (1737), which is credited to Samuel Butler and Laurence Clarke. When looking through this ‘book’, it becomes highly apparent that the first page of text resembles in almost every particular an eighteenth-century newspaper, with columns and an imprint. What is unusual, however, is the title; Exposition on the Common Prayer by Laurence Clarke, no. III (Wednesday 3 August 1737). Identification of the original source of this volume provides further clues as to what is presented by Google. The ‘book’ is a digitised copy of an original volume at the Bodleian Library (Johnson d.1717), whose catalogue provides the same details of author(s) and title as Google Books. An additional and crucial detail that the Bodleian catalogue provides, however, are the notes that the volume comprises ‘The outer sheets only, containing S. Butler’s Hudibras and items of news’. So, what are we dealing with?

Internal evidence within the volume reveals that two works by Laurence Clarke, Exposition of the Common Prayer, and the History of the Holy Bible had been produced concurrently in the summer of 1737, and were to be offered to potential customers in serialised form which could be collected by readers and bound into a book. An advertisement for the History of the Holy Bible gave details of the enterprise, which was to make up two volumes in around one hundred numbers.

One Sheet in Quarto, neatly stitched up in large Covers, on which Covers will be printed the freshest News Foreign and Domestick, as in the Daily Papers, will be published every Wednesday.[1]

If the allure of being provided with the latest news gratis along with this publication was not enough, the sheets were to be embellished with occasional cuts, and Clarke also promised to provide his readers with the additional incentive of a new serialisation of Samuel Butler’s Hudibras, accompanied by its own engravings by Hogarth. This package was advertised for ‘the Perusal of all Families, being very proper for instructing Children in the Rudiments of the Christian Religion’, and priced at two pence per sheet, so that the ‘poorer sort’ might have access to the works.[2] Whilst the news sheets do not bear a printers name, shortly thereafter the London printer Robert Walker attached Clarke’s works to a number of his newspapers marketed to areas outside of London, with titles such as The Warwickshire and Staffordshire Journal: with the History of the Holy Bible, which gave equal prominence to both the newspaper and the serialised publication which came as a supplement.[3] The inclusions of serialised religious texts were intended by newspaper printers to promote circulation and subscription to their titles, and are an example of many such offers made to customers of the mid-eighteenth century. Maps and song-sheets were also offered at premium prices or given away freely. The printers also anticipated other benefits, insofar that by wrapping other publications with news content, they hoped to be exempted from additional newspaper taxes – Walker managed this for ten months before the Commissioners of the Stamp Office insisted that he used stamped paper for his half-sheet news wrappers.[4] These ambitious commercial techniques were not without contemporary criticism. In Derby, Clarke’s History of the Bible was blasted as being ‘pirated’, and the claims that Walker’s papers produced in London could provide more up-to-date news than a country journal were branded ‘ridiculous’.[5]

This example provides a fascinating insight into the range of approaches taken by authors, printers and (more particularly) publishers of newspapers to reach their target audience in the mid-eighteenth century. The 1737-1738 ‘Exposition of the Common Prayer’ volume is anomalous to our usual understanding of newspaper collections of the period, generally defined by locality or individual title. Its presence and inaccurate indexing on Google Books only adds to this curiosity, but conversely, also gives readers the opportunity to investigate this particular aspect of news serialisation of the eighteenth-century – even if it is hidden in plain sight.

[1] Clarke, Laurence, Exposition of the Common Prayer, no. III (London, Wednesday 3 August 1737).

[2] Ibid.

[3] The Warwickshire and Staffordshire Journal: with the History of the Holy Bible, no. LXXXII (London: 8 March 1739). Other titles which carried the History of the Bible included Walker’s Lancashire Journal, and potentially the Hull Courant (founded 1739), although this was printed locally in Hull. See, Wiles, R. M., Freshest Advices, Early Provincial Newspapers in England (Ohio State University Press, 1965), pp. 109-110; Page, W. G. B., ‘Notes on Hull Authors, Booksellers, Printers, and Stationers, etc.’, in, Karslake, Frank (ed.), Book Auction Records, vol. 6, part 1, Oct. 1 to Dec. 31 1908 (London: Karslake & Co., 1909), pp. i-vii. No issue of this date survives, but it is likely that Page had access to copies of the Hull Courant which were known to exist at the turn of the twentieth century, but are now lost.

[4] Wiles, R. M., Freshest Advices, Early Provincial Newspapers in England (Ohio State University Press, 1965), p. 112.

[5] Derby Mercury, vol. VII, no. 15 (Derby: Thursday 29 June 1738).